Halifax Explosion - The Anatomy of a Disaster

Debunking the 13 Mile Myth

Debunking the 13 Mile Myth

Even before I began to intensify my research into the Halifax Explosion photograph, it seemed logical that this image had been taken from somewhere in Bedford Basin looking toward the Southeast. After a lot more work along with the insight of Pierre Richard, I also came to the conclusion that the photo was taken within the one-mile radius of the explosion. That specific result of the investigation took a bit of a shift in thinking. However, the evidence spoke for itself and did not leave much room for any other reasonable conclusion.

Still. I remained curious as to how the 13 mile myth came to be. This myth puts forward the notion that the Halifax Explosion photograph (a print by Underwood & Underwood shown below) was taken from a distance of 13 miles with a POV looking to the Northwest and Bedford Basin; suggesting an area anywhere in the approaches to Halifax Harbour from Chebucto Head on the West to Eastern Passage and beyond.

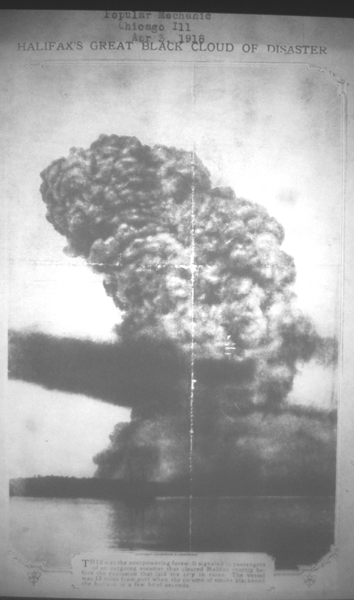

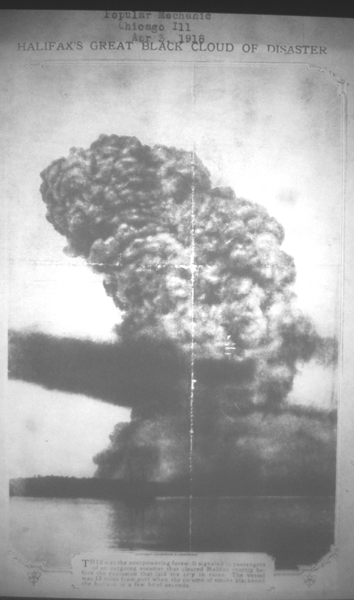

A year later, with some guidance from Garry Shutlak, Senior Archivist at Nova Scotia Archives and Record Management, I am finally able to pinpoint at least one likely source of the 13 mile myth. It's beginnings can be almost certainly be traced back to a photo and short caption that appeared in the April, 1918 issue of the Chicago magazine Popular Mechanics and most likely picked up and circulated by other American publications. Shown below is the cover of that issue.

Still. I remained curious as to how the 13 mile myth came to be. This myth puts forward the notion that the Halifax Explosion photograph (a print by Underwood & Underwood shown below) was taken from a distance of 13 miles with a POV looking to the Northwest and Bedford Basin; suggesting an area anywhere in the approaches to Halifax Harbour from Chebucto Head on the West to Eastern Passage and beyond.

A year later, with some guidance from Garry Shutlak, Senior Archivist at Nova Scotia Archives and Record Management, I am finally able to pinpoint at least one likely source of the 13 mile myth. It's beginnings can be almost certainly be traced back to a photo and short caption that appeared in the April, 1918 issue of the Chicago magazine Popular Mechanics and most likely picked up and circulated by other American publications. Shown below is the cover of that issue.

The page featuring the Halifax Explosion photograph is contained in one of two scrapbooks that were put together at the time by a member or members of the Halifax Relief Commission and can be viewed on microfilm housed at NSARM (MG 20, Volume 529 No. 1, page 186, mfm 23,033). The scrapbooks are filled with many newspaper articles, from Nova Scotia and elsewhere, all relating to the Halifax Explosion. This particular page is entitled, Halifax's Great Black Cloud of Disaster. The date on the accompanying card reads: "Popular Mechanic Chicago Ill Apr 3, 1918". The caption at the bottom of the page (shown below) reads:

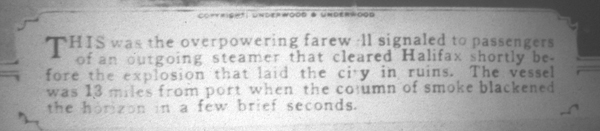

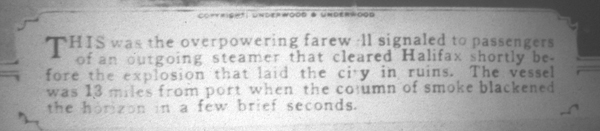

This was the overpowering farewell signalled to passengers of an outgoing steamer that cleared Halifax shortly before the explosion that laid the city in ruins. The vessel was 13 miles from port when the column of smoke blackened the horizon in a few brief seconds. (Note: the word, "signalled" is spelled incorrectly)

This was the overpowering farewell signalled to passengers of an outgoing steamer that cleared Halifax shortly before the explosion that laid the city in ruins. The vessel was 13 miles from port when the column of smoke blackened the horizon in a few brief seconds. (Note: the word, "signalled" is spelled incorrectly)

It should be noted that this version of the photo is highly retouched and is similar to the one that appears in David Flemming's book on the Halifax Explosion. The copyright holder of the photograph, Underwood & Underwood appears above the caption. This only serves to indicate that the photograph was being widely circulated at the time, thereby allowing editors in any location to affix to it whatever copy they deemed appropriate.

From 1918 on, this concept has has apparently continued to pervade local lore. Popular Mechanics was a well-known, widely distributed and even respected publication of the day. There would have been no reason for anyone to have doubted the veracity of the photo page's content even though it does not credit the photographer, mention the name of the steamer or detail the source of the information on distance or direction. These specific notions of distance and direction were also introduced at an early date - within four months of the Halifax Explosion and two months after the conclusion of the Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. With nothing to contradict it, the myth established a foothold.

The caption is but a few simple, unsubstantiated sentences and contains neither scientific nor proven commentary. Yet, this sketchy presentation somehow gained credibility and has been accepted by some authors, historians and the general public as fact. Even the National Library and Archives of Canada continues to perpetuate the myth with its online description of the photograph. (see the top of Page 5)

Read this 50 year anniversary piece from a 1967 issue of Popular Mechanics entitled, The Biggest Blast Before the A-Bomb, a brief Classics Illustrated-type summary of Michael Bird's book, The Town That Died. The injection of hyperbole and the writer's personal lack of knowledge about the event - "a city was blown off the map" - are evident in the first few lines. It should be noted that the Trinity atomic bomb blast of July 16, 1945, produced a yield of 21,000 tons of TNT. The Halifax Explosion produced a yield of nearly 3,000 tons of TNT, about one seventh the strength.

Many well written, sometimes detailed articles were printed about the Halifax disaster by North American newspapers. However, the vague, undocumented content of a single caption printed in a popular magazine from Chicago in purporting the 13 mile myth, should not be given any credence whatsoever.

All of our research to date on this project points to the Halifax Explosion photograph as being take from a vessel situated in Bedford Basin looking southward to the Narrows. We have put forth the argument that had the explosion in the photograph looked as it did from a distance of 13 miles away, it most certainly would have had a higher yield than a 2.9 kiloton blast and would have done considerably more damage to a much wider area.

To really put the kibosh on the 13 mile myth, I went to the N. S. Archives to check the Pickford & Black records which detailed all cargo and passenger traffic in and out of Halifax Harbour. Any passenger steamers leaving Halifax on the morning of December 6, 1917 - between the time the wartime harbour security nets were lifted, around 7:30 am, and 9:04:35 am, the time of the explosion - would not have left the harbour unnoticed and would have been listed in these records.

I cross-referenced two separate Pickford & Black ledgers from the same time period. The records showed that thirteen ships (one of the ledgers mentions fifteen), including the "mysterious American tramp steamer", Clara (see Page 3), were listed as arriving in Halifax on Thursday, December 6. The ledgers showed no record whatsoever of any passenger or cargo ships leaving Halifax Harbour on December 6, 1917. According to one of the ledgers, the first vessel to leave port after the explosion was the next day on Friday, December 7 - a Norwegian ship, Kongfos under Captain J. V. Olsen, which left for Sandy Hook.

The Popular Mechanics caption stated that the blast cloud was "the overpowering farewell signalled to passengers of an outgoing steamer that cleared Halifax shortly before the explosion". The records from Pickford and Black clearly refute this assertion, proving this 1918 caption was a sensationalistic contrivance of the time.

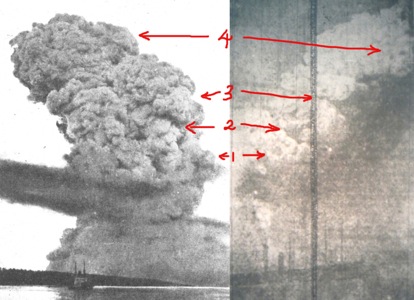

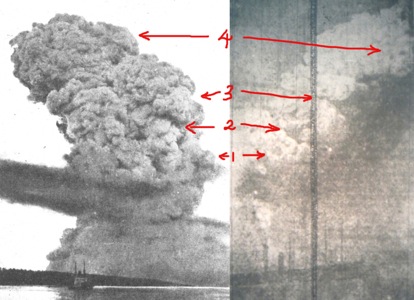

A comparison of the photographs below will further prove that the 13 mile myth lacks any credibility and that the blast/boat photo (left) was taken (15-20 seconds after the blast) within a mile and a quarter of the explosion in Bedford Basin looking to the Southeast.

The documented photo on the right was taken by Ernest McPeak - a member of the crew of the ship, Tyrian, approximately 10 seconds after the explosion - from the Western side of Bedford Basin, probably off of Rockingham Station (see page 6, Item 2b.) looking southeast but more eastward. Even though the quality of the McPeak image is not good, there is still enough contained within the image to make reasonable comparisons.

I have indicated four very distinct points of similarity. Once these points are examined carefully, one can only conclude that both of these photos - taken roughly five to ten seconds apart - were taken in Bedford Basin; 1) from the back of the blast looking Southeast (boat/explosion photo) and 2) from the back and to the right side of the blast with no benzol arm shooting out (Tyrian). The identical shape of the cloud formation labelled example #3 is especially noteworthy.

From 1918 on, this concept has has apparently continued to pervade local lore. Popular Mechanics was a well-known, widely distributed and even respected publication of the day. There would have been no reason for anyone to have doubted the veracity of the photo page's content even though it does not credit the photographer, mention the name of the steamer or detail the source of the information on distance or direction. These specific notions of distance and direction were also introduced at an early date - within four months of the Halifax Explosion and two months after the conclusion of the Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. With nothing to contradict it, the myth established a foothold.

The caption is but a few simple, unsubstantiated sentences and contains neither scientific nor proven commentary. Yet, this sketchy presentation somehow gained credibility and has been accepted by some authors, historians and the general public as fact. Even the National Library and Archives of Canada continues to perpetuate the myth with its online description of the photograph. (see the top of Page 5)

Read this 50 year anniversary piece from a 1967 issue of Popular Mechanics entitled, The Biggest Blast Before the A-Bomb, a brief Classics Illustrated-type summary of Michael Bird's book, The Town That Died. The injection of hyperbole and the writer's personal lack of knowledge about the event - "a city was blown off the map" - are evident in the first few lines. It should be noted that the Trinity atomic bomb blast of July 16, 1945, produced a yield of 21,000 tons of TNT. The Halifax Explosion produced a yield of nearly 3,000 tons of TNT, about one seventh the strength.

Many well written, sometimes detailed articles were printed about the Halifax disaster by North American newspapers. However, the vague, undocumented content of a single caption printed in a popular magazine from Chicago in purporting the 13 mile myth, should not be given any credence whatsoever.

All of our research to date on this project points to the Halifax Explosion photograph as being take from a vessel situated in Bedford Basin looking southward to the Narrows. We have put forth the argument that had the explosion in the photograph looked as it did from a distance of 13 miles away, it most certainly would have had a higher yield than a 2.9 kiloton blast and would have done considerably more damage to a much wider area.

To really put the kibosh on the 13 mile myth, I went to the N. S. Archives to check the Pickford & Black records which detailed all cargo and passenger traffic in and out of Halifax Harbour. Any passenger steamers leaving Halifax on the morning of December 6, 1917 - between the time the wartime harbour security nets were lifted, around 7:30 am, and 9:04:35 am, the time of the explosion - would not have left the harbour unnoticed and would have been listed in these records.

I cross-referenced two separate Pickford & Black ledgers from the same time period. The records showed that thirteen ships (one of the ledgers mentions fifteen), including the "mysterious American tramp steamer", Clara (see Page 3), were listed as arriving in Halifax on Thursday, December 6. The ledgers showed no record whatsoever of any passenger or cargo ships leaving Halifax Harbour on December 6, 1917. According to one of the ledgers, the first vessel to leave port after the explosion was the next day on Friday, December 7 - a Norwegian ship, Kongfos under Captain J. V. Olsen, which left for Sandy Hook.

The Popular Mechanics caption stated that the blast cloud was "the overpowering farewell signalled to passengers of an outgoing steamer that cleared Halifax shortly before the explosion". The records from Pickford and Black clearly refute this assertion, proving this 1918 caption was a sensationalistic contrivance of the time.

A comparison of the photographs below will further prove that the 13 mile myth lacks any credibility and that the blast/boat photo (left) was taken (15-20 seconds after the blast) within a mile and a quarter of the explosion in Bedford Basin looking to the Southeast.

The documented photo on the right was taken by Ernest McPeak - a member of the crew of the ship, Tyrian, approximately 10 seconds after the explosion - from the Western side of Bedford Basin, probably off of Rockingham Station (see page 6, Item 2b.) looking southeast but more eastward. Even though the quality of the McPeak image is not good, there is still enough contained within the image to make reasonable comparisons.

I have indicated four very distinct points of similarity. Once these points are examined carefully, one can only conclude that both of these photos - taken roughly five to ten seconds apart - were taken in Bedford Basin; 1) from the back of the blast looking Southeast (boat/explosion photo) and 2) from the back and to the right side of the blast with no benzol arm shooting out (Tyrian). The identical shape of the cloud formation labelled example #3 is especially noteworthy.

I think the image and caption below are the best evidence to blast away the 13 mile myth. It is a copy of the original photo from which all others have been derived. This image is from the February 14th, 1918 issue of "Church Work", a periodical put out by the Anglican Archdiocese that I discovered amongst the papers of Archibald McMechan. Much more water is visible, allowing for better perspective. Unlike the rough sea off the harbour approaches, where no such spit of land in the background exists, the calmness of the water is even more evident in this image. The reflection in the water also allows for a calculation of distance which, according to all known data, is roughly one and a quarter miles distant from the blast cloud.

The caption refers to the photograph being taken from a ship "entering the harbour". It seems more likely that the photo was taken from the guard ship, Acadia, which was permanently moored in that part of Bedford Basin. This photo and the one above from "Popular Mechanics" say two different things - one ship is entering the harbour, the other is leaving. The caption wording could easily have been mixed up when the photo was widely distributed. However, the fact remains: the location itself is not consistent with any land or water on the oceanside entrance to Halifax Harbour.

The photograph on the right is a composite of the Underwood & Underwood photo and the newspaper clipping from "Church Work" (see Photo 3. on Page 5, "The Anatomy of a Disaster"). I have put forth the theory that the photograph itself may have been taken by accredited Mi'kmaw photographer, Joseph Cope, who was recorded in the oral tradition as having been in the area in the immediate aftermath of the explosion.

The majority of the photographs on this website were obtained from the Internet

or created by Pierre Richard or Joel Zemel. Exceptions are listed on Page 5.

If anyone sees an image on this website that is incorrectly credited

or where due credit is omitted, or believes there is an existing copyright issue,

please contact me through the "Contact SVP" link.

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Names Page Debunking the 13 Mile Myth

The caption refers to the photograph being taken from a ship "entering the harbour". It seems more likely that the photo was taken from the guard ship, Acadia, which was permanently moored in that part of Bedford Basin. This photo and the one above from "Popular Mechanics" say two different things - one ship is entering the harbour, the other is leaving. The caption wording could easily have been mixed up when the photo was widely distributed. However, the fact remains: the location itself is not consistent with any land or water on the oceanside entrance to Halifax Harbour.

The photograph on the right is a composite of the Underwood & Underwood photo and the newspaper clipping from "Church Work" (see Photo 3. on Page 5, "The Anatomy of a Disaster"). I have put forth the theory that the photograph itself may have been taken by accredited Mi'kmaw photographer, Joseph Cope, who was recorded in the oral tradition as having been in the area in the immediate aftermath of the explosion.

The majority of the photographs on this website were obtained from the Internet

or created by Pierre Richard or Joel Zemel. Exceptions are listed on Page 5.

If anyone sees an image on this website that is incorrectly credited

or where due credit is omitted, or believes there is an existing copyright issue,

please contact me through the "Contact SVP" link.

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Names Page Debunking the 13 Mile Myth

| Main | Jazz Guitar | Shakespeare Sonnets | About SVP/HalifaxExplosion.net | Links | SVP News | Contact SVP |

![]() 2009-2013 SVP Productions. All text protected. All rights reserved.

2009-2013 SVP Productions. All text protected. All rights reserved.